Yiddish

Language as Ally and Enemy

The story of Yiddish in modern times is not only the story of a language but also the story of a cultural battlefield. It has been embraced by some as a faithful ally of Jewish identity and resisted by others as an enemy to progress or faith. Few languages have been so passionately fought for and against, with every poem, play, newspaper, or school lesson standing as both a celebration and a challenge. Yiddish was never a neutral tool of communication. It carried with it questions of authenticity, power, and survival. Across Europe and beyond, Yiddish became a symbol of both loyalty to the Jewish people and resistance to their aspirations. Its rise, flourishing, and struggles reveal how language can embody cultural identity while also provoking intense opposition.

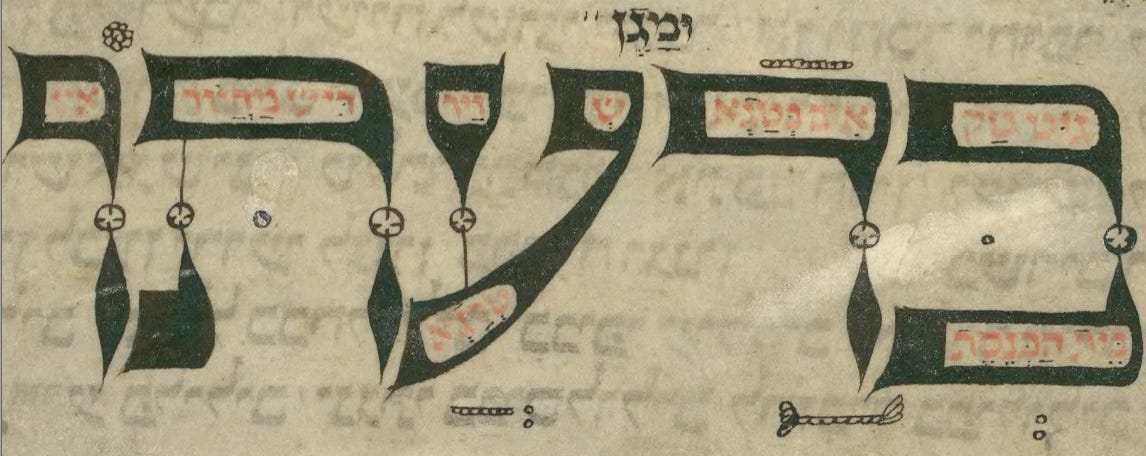

To understand why Yiddish was fought over, one must first recall its origins as the spoken tongue of millions of Jews in Eastern Europe. For centuries it was the vernacular language of family, street, and market. Yet it lacked prestige. Hebrew was language of prayer and study, while German, Russian, and Polish were seen as the languages of education, advancement, and belonging in the wider world. Yiddish stood between them, beloved and despised. Elites sneered at it as a “jargon,” while ordinary Jews simply spoke it. When intellectuals of the nineteenth century began to claim Yiddish as a cultural treasure, they were not merely writing stories. They were making a political statement that what the masses used could be worthy of literature, education, and national identity. This step triggered both admiration and resistance.

An early example of this struggle can be found in the Russian Empire during the late nineteenth century. At that time Jewish writers such as Mendele Mocher Sforim, Sholem Aleichem, and I. L. Peretz began to craft modern literature in Yiddish. Their choice of language was radical because it challenged two sets of opponents. On one side, traditionalists insisted that Hebrew should remain the cultural medium, since it was linked to scripture and the continuity of the Jewish people. On the other side, assimilationists argued that Jews should abandon Jewish languages entirely and adopt Russian or German in order to integrate into modern society. Yiddish literature thus had enemies both within and outside the Jewish community. Yet its supporters fought for it precisely because it was the language of the people. They believed that only by using the vernacular could modern Jewish literature speak honestly to the lives of ordinary men and women. As David E. Fishman notes in The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture, the emergence of these writers

conferred dignity on the despised ‘jargon’ and demonstrated its potential as a literary language .

The theater magnified this conflict. Yiddish plays drew enormous audiences in towns and cities across Eastern Europe. The stage gave ordinary people access to stories, songs, and satire in their own tongue. For supporters of Yiddish culture this was evidence that the language was alive, creative, and unifying. For opponents, the theater was proof of its vulgarity. Rabbis condemned it for frivolity, while assimilationists dismissed it as low entertainment that confirmed stereotypes of Jewish backwardness. As Fishman explains, the Yiddish theater was “attacked as debased and vulgar” but simultaneously thrived because it “spoke to the lives of ordinary Jews” . The popularity of Yiddish theater turned every performance into a statement. To sit in the audience was to ally oneself with the cause of the mother tongue. To shun the theater was to side with those who believed Yiddish belonged at best in the kitchen and the marketplace, not on the stage of serious culture.

The struggle for and against Yiddish was not confined to Russia. In Poland, after the First World War and the collapse of empires, the cultural battle took on new urgency. Jews were granted rights of association, and schools became the frontline of conflict. Secular Yiddish schools were established to teach history, science, and literature in Yiddish rather than in Hebrew or Polish. Supporters saw these schools as essential for giving children an education in their own voice, tying modern knowledge to Jewish cultural continuity. Opponents, however, insisted that education in Yiddish would trap Jewish youth in provincialism and separate them from the wider nation. Zionists promoted Hebrew schools as preparation for life in Isreal, while assimilationists argued for Polish-language schools as a path to civic inclusion. Fishman stresses that the Yiddish school movement “was an assertion of the right of the Jewish vernacular to function as a vehicle for high culture and modern education” . Every classroom thus became a contested space.

The Yiddish press in Poland reflected these battles. Newspapers in Yiddish reached hundreds of thousands of readers and became platforms for political parties, labor movements, and cultural debates. They fought for the right of Jews to see their lives and struggles reflected in their own tongue. Yet the very existence of such a press drew criticism. Nationalists accused Yiddish of perpetuating Jewish separateness, while Hebraists condemned it as a distraction from the revival of Hebrew. Supporters of the Yiddish press argued that newspapers in Russian or Polish could never reach the entire community with the same immediacy. Detractors replied that newspapers in Yiddish only deepened the ghetto walls. As Fishman points out, “The Yiddish press became the main vehicle for the spread of modern culture among the masses” and therefore a battleground over Jewish identity .

Beyond Eastern Europe, Yiddish also provoked struggles in the United States. Jewish immigrants carried Yiddish across the Atlantic, where it became the language of newspapers, schools, and political activism in immigrant neighborhoods. Yiddish was fought for in America by those who used it to organize labor unions, to publish socialist journals, and to preserve cultural heritage in the face of rapid Americanization. Yet it was fought against by both external and internal forces. Mainstream American society expected immigrants to assimilate and adopt English. Within the Jewish community itself, upwardly mobile families encouraged their children to drop Yiddish in favor of English as a mark of progress. Supporters defended Yiddish as the key to solidarity among workers and as a link to their parents’ world. Opponents feared it would chain Jews to the immigrant ghetto and prevent full acceptance into American life. In Fishman’s words, Yiddish in America was

embraced as a badge of solidarity but spurned as a mark of backwardness.

The fight over Yiddish reached its sharpest point in the clash between Yiddishists and Hebraists. Yiddishists saw in the vernacular the soul of the Jewish nation. They argued that it expressed the joys, sorrows, and wit of generations and could serve as the foundation of a secular Jewish identity. Hebraists rejected this claim, insisting that Hebrew alone could be the national language, both ancient and modern. In Isreal this conflict was especially fierce. The revival of Hebrew as a spoken tongue was one of the triumphs of Zionism, but it came at the cost of marginalizing Yiddish. Public signs, schools, and even daily speech became arenas where Yiddish was discouraged or mocked. To speak Yiddish in the streets of Tel Aviv was to risk being told to “speak Hebrew.” In this context Yiddish became an enemy to the Zionist project, even as Yiddishists fought to keep it alive through theaters, journals, and schools. As Fishman observes, the language wars in Isreal

turned Yiddish into the symbol of the diaspora past, while Hebrew was the banner of the national future.

The catastrophe of the Holocaust devastated Yiddish culture, wiping out communities where it had flourished. In this sense the enemies of Yiddish were no longer only ideologues or intellectuals but the forces of annihilation. Yet even after the war the struggle continued. Survivors in camps published newspapers in Yiddish and staged plays as acts of resistance and continuity. They fought to prove that Yiddish was not dead, that it could still be a voice of survival. At the same time, assimilation pressures in America and Western Europe, along with the dominance of Hebrew in Israel, made Yiddish appear obsolete to many. In these societies Yiddish was often treated as an embarrassing relic rather than a living ally. The fight for Yiddish after 1945 became a fight against cultural amnesia as much as against external opposition.

In recent decades Yiddish has undergone a partial revival. Academic programs, klezmer music, and Hasidic communities have kept it alive. Yet even here the language is caught between allies and enemies. For some Hasidim Yiddish is an ally that preserves separation from the secular world. For secular revivalists Yiddish is a link to a lost culture that can be rediscovered in libraries and concert halls. For others it remains irrelevant or even a distraction from integration and modernity. The old battles over Yiddish have not disappeared but have simply shifted form.

The history of Yiddish shows how a language can become a contested symbol of identity. In Russia it was fought for as literature and fought against as “jargon.” In Poland it was fought for in schools and fought against as provincialism. In America it was fought for in labor unions and fought against as a barrier to assimilation. In Isreal it was fought for as cultural authenticity and fought against as an obstacle to Hebrew nationalism. Each setting reveals the same paradox: Yiddish was both ally and enemy, embraced by some as the true Jewish voice and rejected by others as a threat to progress.

The struggle over Yiddish teaches us that language is never neutral. It is tied to visions of the past and hopes for the future. Supporters of Yiddish fought for it because they believed it carried the experiences and creativity of the Jewish people. Opponents fought against it because they believed it chained Jews to backwardness or blocked other ideals. Both sides understood that the stakes were high. To defend or reject Yiddish was to defend or reject an entire vision of Jewish identity.

In the end, Yiddish endures as a testimony to those struggles. It survives in classrooms, in music, in Hasidic neighborhoods, and in literature that continues to be read. Its survival is itself a form of victory, even if diminished from the grand dreams of its defenders. It also stands as a reminder of the costs of opposition, of the ways in which a people can fight against its own language. Yiddish remains a story of ally and enemy, fought for and fought against, a language that embodies both resilience and controversy.