A Gate to a Resurrected World: Chaim Grade’s Sons and Daughters

A Review

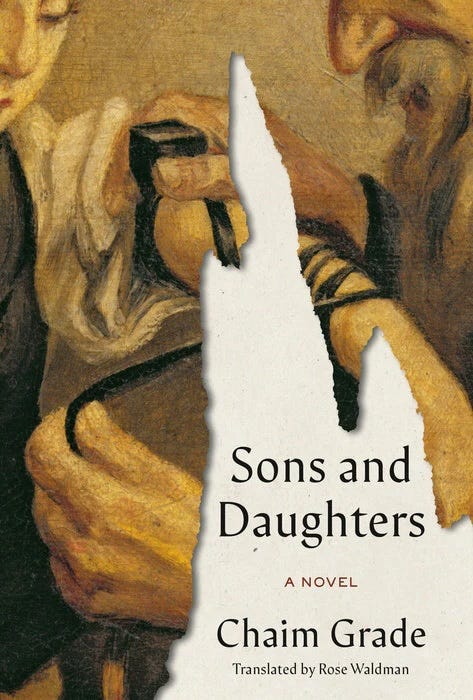

Chaim Grade’s Sons and Daughters, newly translated into English by Rose Waldman, is a monumental work — one that has been described as "the last great Yiddish novel." Originally serialized in Yiddish newspapers in the 1960s and 70s, the novel remained unpublished in book form until now. Set in 1930s Poland, the book captures a Jewish world on the brink of annihilation, though the Holocaust itself remains an unspoken shadow. Grade, a Holocaust survivor, writes with the urgency of a witness preserving a vanishing culture.

For a non-Jewish readers, Sons and Daughters offers a profound and immersive experience — not just as a historical document, but as a deeply human story of generational conflict, faith, and the painful transition from tradition to modernity. It is a novel that speaks to universal themes — family strife, the erosion of old ways, and the search for meaning — while remaining firmly rooted in the specific struggles of Eastern European Jewry.

The novel centers on the Katzenellenbogen family, led by Rabbi Sholem Shachne, a devout and learned man struggling to uphold tradition in a rapidly changing world. His children, however, are pulling away in different directions. Naftali Hertz, the eldest son, abandons yeshiva for secular studies in Switzerland, marries a non-Jewish woman, and severs ties with his family. The middle son, Bentzion, rejects rabbinic scholarship for business, and ended up working in a garment shop in Bialystok. Refael’ke, the youngest, is drawn to Zionism and dreams of emigrating to Palestine. The elder daughter, Tilza is unhappily married to a rigid yeshiva head, yearning for romantic fulfillment. Bluma Rivtcha, the younger daughter, resists an arranged marriage to Zindel Kadish, a would-be rabbi who dreams of a modernized Judaism in America.

The central tension is the clash between the old world — where piety, study, and communal duty define life — and the new, where individualism, secular education, and political ideologies (Zionism, socialism, assimilation) promise liberation. Grade does not present this conflict simplistically; neither the traditionalists nor the modernizers are entirely right or wrong. Instead, he explores the emotional and philosophical costs of these choices with remarkable nuance.

Grade’s prose, rendered beautifully in Waldman’s translation, is richly descriptive, steeped in the textures of Jewish life — the creaking floors of the rabbi’s house, the murmuring willows outside, the stifling heat of study halls, the melancholy of a riverbank at dusk. His characters are vividly drawn, their inner lives laid bare with psychological precision. Sholem Shachne is a tragic figure, a man who has devoted his life to Torah but finds himself powerless as his children reject his world. His sorrow is not just personal but existential — he sees the collapse of a civilization. Grade’s portrayal is deeply sympathetic, yet he does not shy away from the rabbi’s flaws: his rigidity, his inability to understand his children’s desires, his quiet despair.

Each of the rabbi’s children embodies a different response to modernity. Naftali Hertz represents intellectual assimilation, abandoning Jewish particularism for European philosophy. Bentzion opts for practicality, trading Talmud for commerce, yet remains emotionally adrift. Refael’ke turns to Zionism, seeking a Jewish future outside the diaspora. Tilza yearns for personal happiness, trapped in a loveless marriage. Bluma Rivtcha is the most conflicted—she rejects both her father’s piety and Zindel’s half-hearted modern Orthodoxy, yet has no clear alternative. Grade’s genius lies in how he refuses to villainize any of them. Their rebellions are understandable, even inevitable, yet their paths are fraught with uncertainty.

For non-Jewish readers, Sons and Daughters is more than a historical curiosity. It is universal family saga when readers get to see the tensions between parents and children, tradition and progress, are timeless; a meditation on cultural loss in an era of globalization, many cultures face similar struggles to preserve identity; a warning against dogmatism as we track how the rabbi's inability to adapt alienates him from his children; and a reminder that treasures abound in hidden places - Yiddish have more to offer us.

Sons and Daughters is not an easy read. Its pacing is deliberate, its emotions restrained, its ending unresolved (Grade intended a second volume that was never completed). Yet it is a profoundly moving work, one that demands patience and rewards it with deep insight. For those unfamiliar with Jewish tradition, the novel may require some effort — words like beis medrash, tzitzis, and shidduch are woven seamlessly into the text but may send some readers to the notes. The notes, fortunately, are inadequate. Readers can see it as an invitation to an immersion into an era and a culture. This immersion is part of the book’s power: it does not explain itself to outsiders but invites them into its world.